#161: The Earth Sauna— First Thread of a Hidden Weave

How Arctic vapor emissions are reshaping Northern Hemisphere climate, from fog belts to jetstreams to melt zones. A journey into the feedbacks the models forgot.

In these episodes, “Moisture emissions (vapor-fog)” is an umbrella term for open-water evaporation, spray and fine droplets from spillways or turbine shear, and the warm humid plume itself. The visible mist is fog, which is liquid microdroplets, while true water vapor is invisible. When warm releases enter very cold, dry air, part of the vapor condenses within the shallow inversion into fog and releases latent heat in the near-surface layer. Fog increases downwelling longwave to ice and open water, reduces net longwave loss, stabilizes the boundary layer, and can accelerate melt or delay refreezing. As sunlight, wind, or mixing act, the fog evaporates to gas phase and the air mass continues as a moist plume that can be advected downwind. When that plume meets lift from fronts, shear, or terrain, condensation aloft releases latent heat higher in the column, adjusts stability and small pressure fields, can nudge storm tracks, and in some sectors increases cold-season precipitation at high latitudes. Aerosol regimes remain important: polar air can be CCN and INP poor, fog can scavenge particles and return them on re-evaporation, and spillway spray can add some nuclei. Throughout the text, “fog,” “vapor-fog plume,” and “Moisture emissions (vapor-fog)” may appear interchangeably; they describe the same continuum, with fog denoting the visible condensed state and vapor the invisible gas phase within the same emission field. This is a terminology correction, not a change to conclusions.

On DOMEs (Domes of Moisture Emissions). The concept and term DOMEs come from Stephen M. Kasprzak, with early scientific warnings by Hans Neu. Kasprzak’s maps, graphs, and core climatological framing underlie the feedbacks discussed here, from sub-Arctic vapor flows and fog belts to snowpack collapse and nutrient starvation. When you see “DOMEs,” read it as Kasprzak’s terminology for the same moisture-emission structures described above. In practice, DOMEs, vapor-fog plumes, and Moisture emissions refer to the same physical system: when visible it is fog, when invisible it is vapor within the same plume.Let’s begin not with satellite data, but with your skin.

You sit in a sauna. The air is dry.

Warm, yes, but not yet immersive.

Then someone pours a ladle of water on the stones.

Ssssshhh.

A hiss. Then a swirl.

The heat doesn’t increase. It changes.

It stops being something you feel on your skin,

and becomes something you feel within.

What just happened?

The water, evaporating, carried with it a hidden payload i.e., 2.45 million joules per kilogram of energy, as latent heat inside each gram of vapor. It didn’t disappear. It traveled (invisible, unmeasured, underestimated) until it condensed again, releasing all its energy instantly, locally, and often unpredictably.

This isn't an analogy for the climate system.

It is the exact mechanism by which water, when transformed into vapor, becomes one of the most powerful atmospheric transport agents on Earth.

Phase Change: The Overlooked Engine of Global Energy Transport

Climate models correctly emphasize radiative imbalance as a central driver of global warming. But in their precision, they often miss the mechanisms by which energy actually moves not just as radiation, but as vapor. Water, through its phase transitions, may be the most under-credited force in the planetary heat engine.

Evaporation is energy storage.

Condensation is energy release.

Each gram of vapor carries 2.45 million joules per kilogram until it finds a place to condense. That moment of condensation does more than form clouds. It alters the structure of the sky.

Here’s why this matters:

Hurricanes explode over warm oceans because evaporating seawater loads the air with latent heat, fueling rapid intensification upon condensation.

Tropical forests self-cool by transpiring vapor, which draws in moist air and regulates local climates.

Steam burns deeper than fire by dumping latent heat directly into tissues, illustrating the raw power of phase change.

But the bigger picture emerged with Anastassia Makarieva and Victor Gorshkov’s biotic pump theory (introduced in their 2007 paper in Hydrology and Earth System Sciences). Forests aren’t passive players in the climate they actively regulate it. Through massive transpiration (evapotranspiration), trees release water vapor that condenses over the canopy, creating low-pressure zones. This “pump” draws moist ocean air inland, sustaining rainfall far from the coasts. It’s physics meets ecology: the forest’s vast leaf surface evaporates more water than an equivalent ocean area, amplifying condensation and pressure drops.

This is not just theory. The model predicts pressure differences, wind vectors, and rainfall patterns with uncanny accuracy in forested regions. The implication is profound: remove the forest, and you not only reduce evapotranspiration, you collapse the mechanism that pulls moisture from sea to land.

Peter Bunyard brought this theory to life with hands-on experiments, detailed in his 2017 and 2019 papers in DYNA and a 2025 Substack analysis. In a sealed glass chamber, he simulated atmospheric conditions: humid air at the bottom, a cooled upper surface to trigger condensation.

The results were striking. Cooling alone (without condensation) produced negligible airflow, less than 0.01 m/s. But when condensation kicked in:

Airflow surged to over

1.0 m/s, sustained and directional.This wasn’t buoyancy from rising warm air. It was an implosive vacuum effect: Water vapor condensing into liquid shrinks by a factor of about 1,700 in volume, creating a local low-pressure “pull” that draws in surrounding air.

Bunyard quantified the forces:

Latent heat release: ~2.26 kJ/g (disperses broadly, warming the air).

Implosive cooling: Just 0.17 kJ/g; but it’s this concentrated volume collapse that drives circulation, much like the vacuum in a Newcomen steam engine.

In the chamber, this generated micro-winds. Scaled up, it mirrors real-world observations: Amazonian forests pull in 10 m/s winds from the Atlantic, transporting moisture thousands of kilometers inland.

And yet, in engineered systems (particularly, those where winter inversions form and air cannot rise) we release vapor without the forest’s pump. Without the canopy. Without the living condensation nuclei that guide the rhythm of ascent and return.

In nature, condensation completes the cycle aloft: moist air climbs, cools, and releases its latent heat high above the ground, drawing new air inward and renewing circulation.

But in inversion-bound systems, the story collapses near the surface. Condensation occurs within a few tens of meters, inside a lid of cold air. The released heat cannot escape upward; it spreads sideways, trapped beneath the inversion, warming but not breathing. It is a heartbeat muffled by its own fog.

So when the sky grows saturated yet cannot resolve its excess,

we witness its paralysis as fog, as inversion, as a stagnant pressure field that silences rain and weakens circulation.

Anastassia Makarieva calls this the biotic heart of the planet—

Peter Bunyard has shown it can beat, and stop.

And the question remains: in the name of clean energy, are we quieting that heart in places where the air itself cannot lift?

But Before the Vapor — The Carbon

Not all emissions come from smokestacks. Some rise from drowned shorelines—where trees rot underwater, peat ferments in the shadows, and long-stored carbon begins to stir.

Hydropower is often sold as clean. Low-carbon. A benign partner in our planetary repair. But the reality beneath the surface is more complicated especially, in cold, boreal latitudes where decomposition slows, and methane waits like a delayed fuse.

In these regions, reservoirs behave less like batteries and more like biogeochemical reactors. Organic matter (trapped under still, anaerobic water) doesn’t simply dissolve. It transforms. Microbes feast. Methanogenesis begins. And in the absence of oxygen, CH₄ (not CO₂) becomes the dominant emission.

And methane, as we know, is no minor character.

It’s more than 80 times more potent than CO₂ over a 20-year horizon.

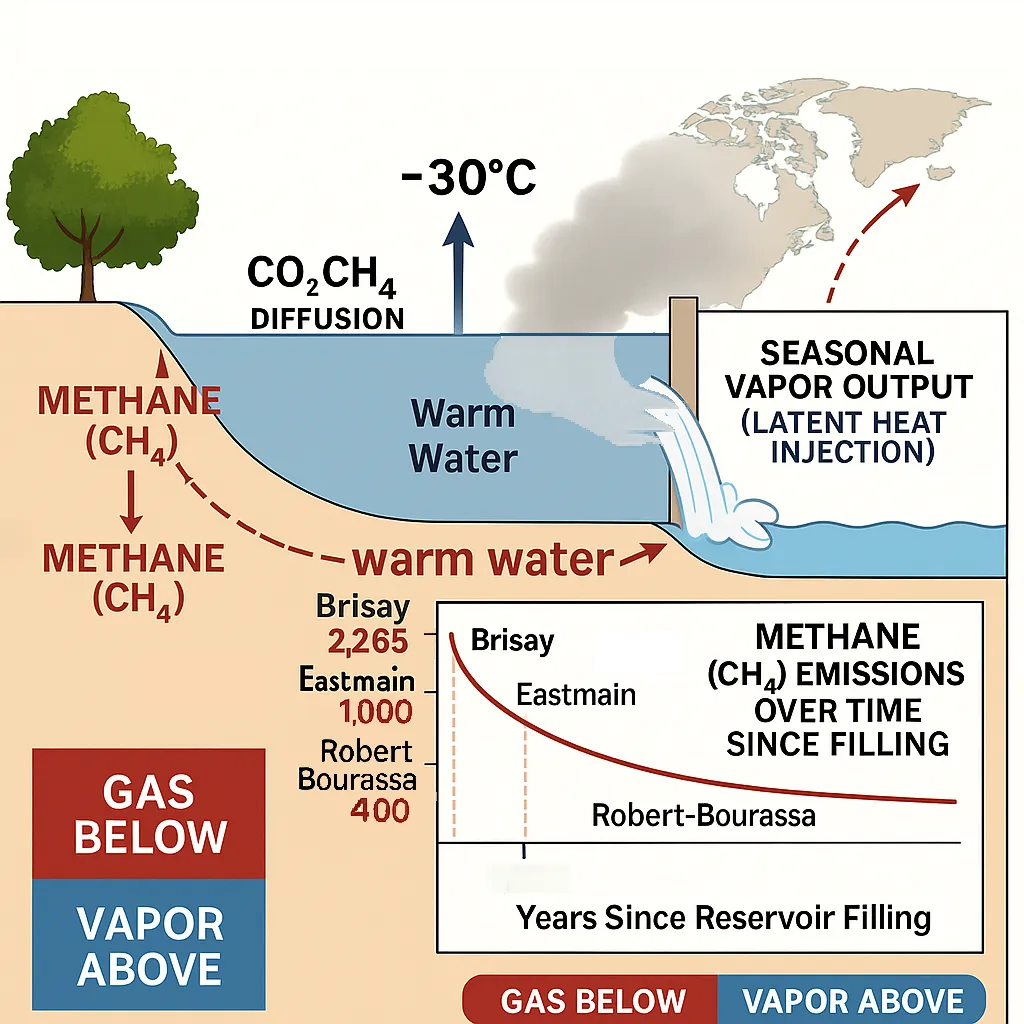

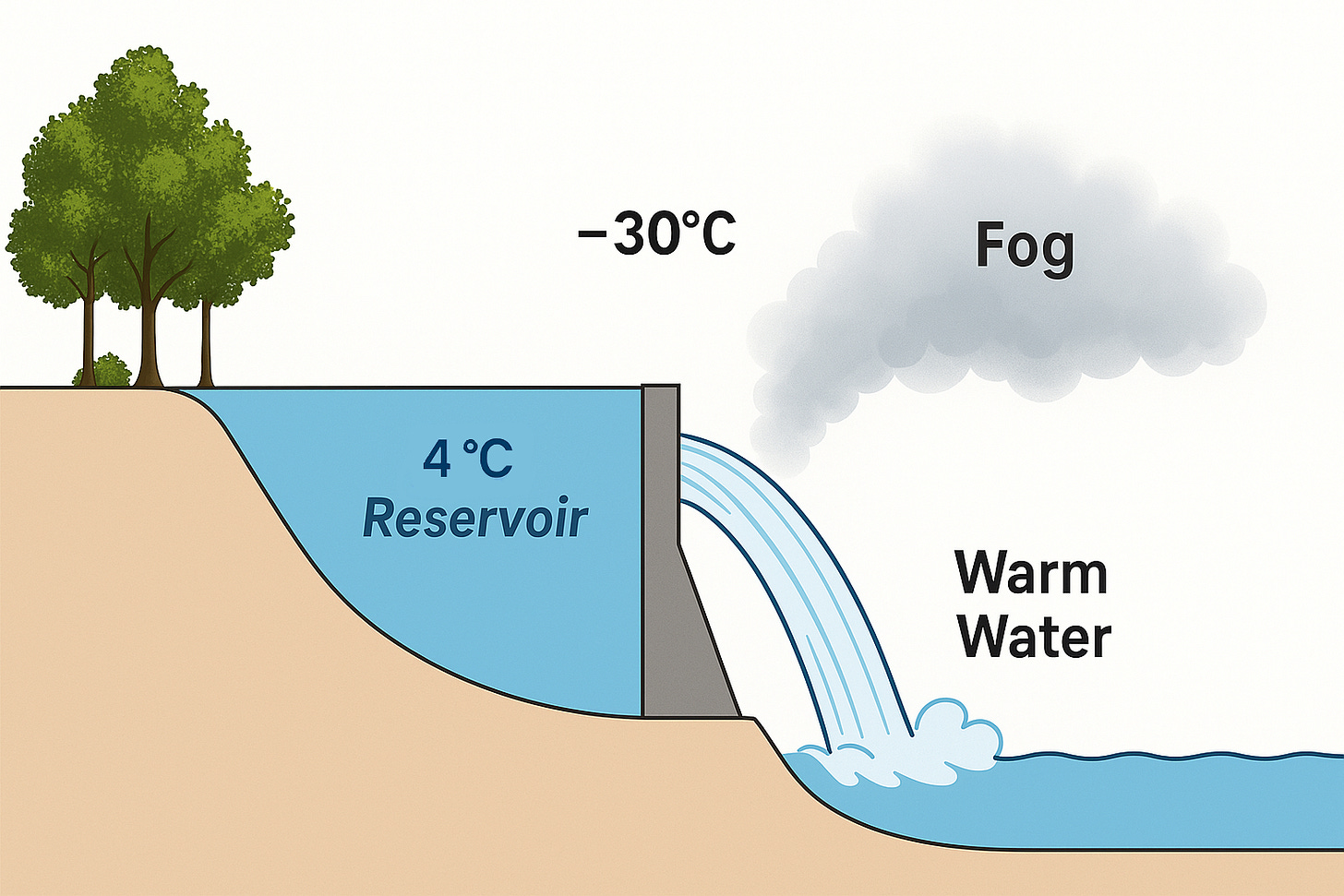

Above the surface, a second emission pathway unfolds: warm water discharged from the dam interacts with -30°C Arctic air, releasing massive amounts of latent heat as vapor. This seasonal pulse of energy (uncounted in carbon inventories) travels downwind, contributing to Arctic amplification. Together, these two flows gas below, vapor above form an infrastructural climate feedback that standard models rarely capture, but nature already feels.

Here’s where the story tightens:

Some of the very same dams implicated in vapor-driven warming also carry some of the highest carbon footprints in the hydropower sector

For instance …

Brisay–Caniapiscau: Estimated lifecycle emissions of 2,265 gCO₂e/kWh, according to Scherer & Pfister (2016), which assessed the full biogenic carbon footprint of hydropower reservoirs in boreal zones.

Robert-Bourassa: Produces around 400 gCO₂e/kWh, as noted by Barros et al. (2011) and confirmed in Hydro-Québec’s internal assessments reported by McCully (1996).

Eastmain-1: In its first year, emitted at coal-equivalent levels (approaching 1,000 gCO₂e/kWh), before declining to natural gas levels (~400 gCO₂e/kWh) by year three, as documented in Teodoru et al. (2012).

These aren’t obscure or outdated installations. They are the crown jewels of Quebec’s hydroelectric fleet, feeding power into New York, Ontario, and beyond, under the banner of “clean” energy.

And their geography matters. Because these are the very systems that sit beneath the Arctic vapor corridor, the same plume that traces its way toward Greenland.

What this suggests is unsettling but increasingly undeniable:

Some of the most significant contributors to regional Arctic amplification may be dual-mode emitters.

They release long-lived greenhouse gases through their reservoirs — and short-cycle vapor through their turbines.

And both forms of emission—gas and phase-state—interact with the climate system in fundamentally different, yet mutually reinforcing ways.

One warms the planet slowly, persistently. The other modulates the thermal engine of the sky.