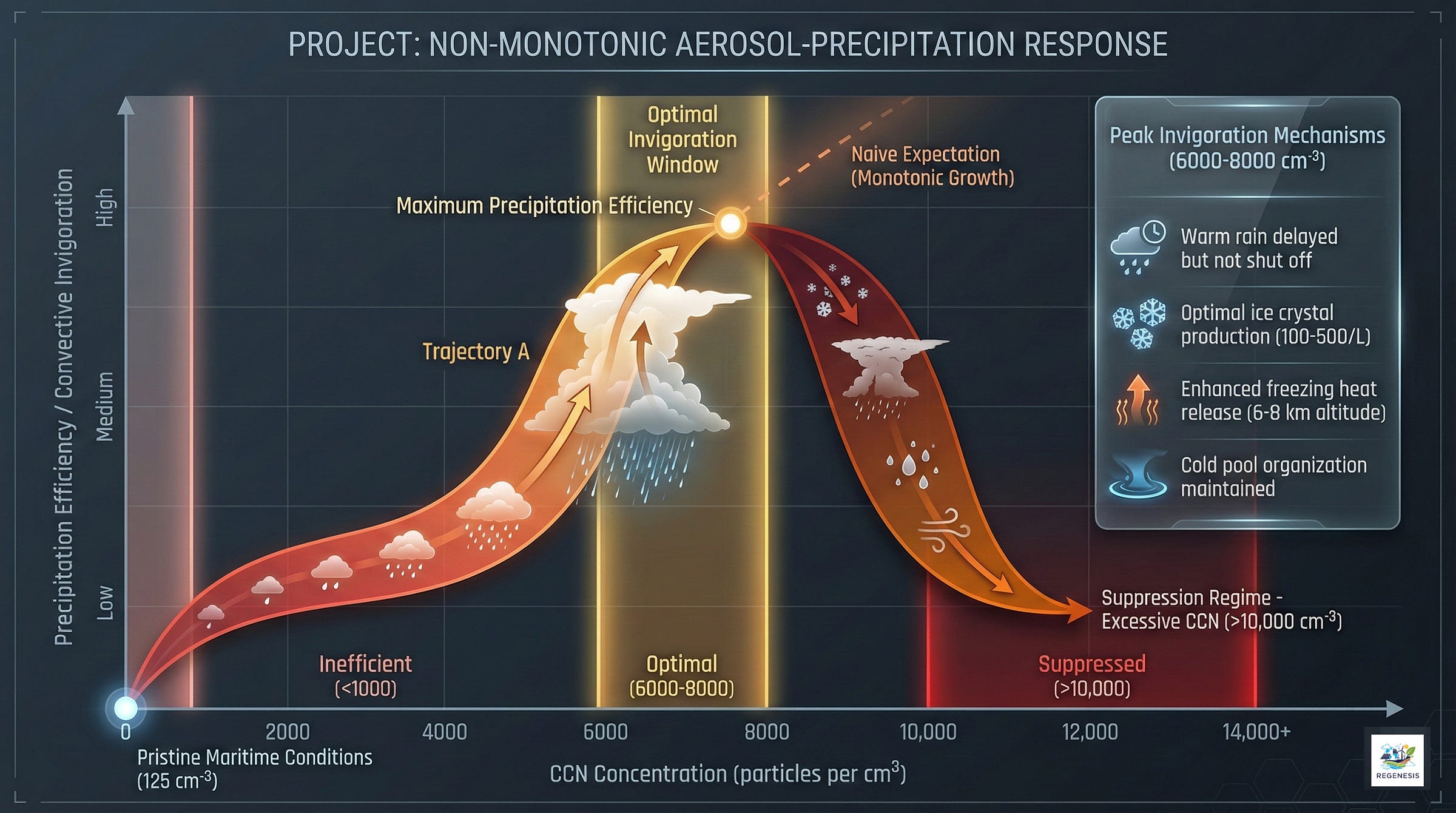

#207: The Aerosol Optimization Window - Why Rainfall Efficiency, Storm Invigoration, and Cold Pool Organization All Peak Between 1,000-8,000 CCN/cm³

Water Phase Transitions and Climate Repair - Part 10: The Inverted U-Curve Where Precipitation Mechanisms Align at Moderate Concentrations and Collapse When You Deviate in Either Direction.

Last time, we built the foundation. We walked through what clouds actually are, why most clouds don’t make rain, how droplet size distributions control everything, what ice processes contribute, and why precipitation mechanisms vary dramatically by region and cloud type.

If you followed Episode 206, you now understand that a 15-micrometer droplet threshold determines whether collision-coalescence can accelerate. You know that the -38°C level creates a hard boundary where all liquid water freezes regardless of ice nucleating particle availability. You understand why cold pools from evaporating rain organize mesoscale convection and why their strength depends on droplet size distributions.

This foundation wasn’t academic. It was necessary. Because now we’re going to examine something that contradicts everyday intuition about atmospheric interventions, something that reveals fundamental limits on what’s possible when you try to modify precipitation.

Here’s the question that seems straightforward until you examine the physics: If aerosols can invigorate convection by suppressing warm rain and releasing latent heat aloft, wouldn’t more aerosols mean stronger invigoration? No.

The relationship between aerosol concentration and convective response is not monotonic. There exists an optimal concentration, typically around 6000 to 8000 CCN/cm³ for cold pool formation, though it varies with storm type and environmental conditions, where invigoration reaches maximum effectiveness. Push beyond that optimum, and the same physical processes that created invigoration begin working in reverse (Feng et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2019).

The storm weakens. Precipitation decreases. The invigoration becomes suppression.

This isn’t theoretical speculation or model artifact. It’s been observed in satellite data of natural storms, reproduced in cloud-resolving simulations with explicit microphysics, documented in hurricane modification research, and measured in field campaigns across multiple continents (Jeon et al., 2018; Zang et al., 2024; Hazra et al., 2013).

Understanding why reveals operational constraints that any serious discussion of precipitation modification, or climate repair through managing aerosol concentrations to restore or prevent precipitation changes (reducing pollution in suppressed regions to restore rainfall, or maintaining low concentrations in pristine areas to prevent unwanted storm invigoration), must address. It explains why Project STORMFURY produced inconclusive results despite years of effort and substantial funding. It demonstrates why hurricane seeding proposals based on simple “more aerosols = more invigoration” logic won’t work as advertised. And it shows that aerosol effects on precipitation operate through regime-dependent mechanisms with sharp transition points rather than smooth monotonic relationships.

This is where physics becomes tactical. Where understanding mechanism reveals what’s possible and what isn’t.

I. The Evidence: Non-Monotonic Responses Across Scales and Systems

A. Tropical Oceanic Convection: Satellite Observations and Cloud-Resolving Models

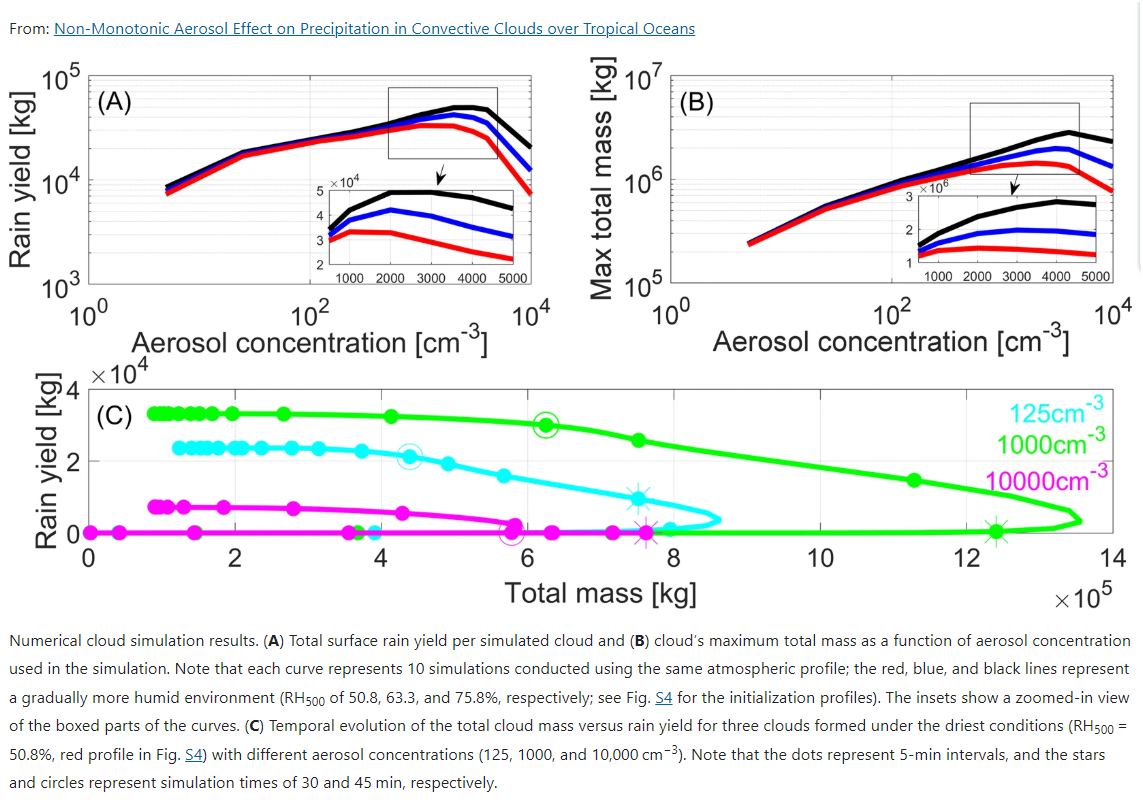

The clearest early documentation of non-monotonic aerosol response came from systematic analysis of tropical convective clouds over oceans. Liu et al., 2019 combined satellite observations with cloud-resolving model simulations to track how tropical convection responds across a wide aerosol concentration range.

The observational analysis used aerosol optical depth (AOD) as a proxy for CCN concentration. Tracking thousands of tropical convective clouds, the data revealed an unexpected pattern. As AOD increased from pristine conditions, cloud top heights increased, maximum cloud mass increased, and rainfall intensified, the expected invigoration signal.

But this strengthening didn’t continue indefinitely. At intermediate AOD values (corresponding to CCN concentrations around 1000 to 2000 cm⁻³), the trend reversed. Further increases in aerosol loading produced shallower clouds, reduced maximum cloud mass, and suppressed precipitation. The relationship formed an inverted U-curve rather than monotonic enhancement (Liu et al., 2019).

Cloud-resolving model simulations confirmed and explained this pattern. Runs with aerosol concentrations ranging from 5 to 10,000 cm⁻³ were conducted under idealized tropical thermodynamic profiles representing different humidity conditions. For each profile, total surface rain yield and maximum cloud mass showed clear peaks at intermediate concentrations rather than continuing to increase with aerosol loading (Liu et al., 2019).

The simulations revealed the mechanism. Follow a single cloud through its evolution at three different aerosol concentrations:

Pristine conditions (125 cm⁻³): Large droplets form quickly. Collision-coalescence initiates early, by 15 minutes into simulation. Rain reaches the surface before substantial condensate ascends to freezing levels. The cloud produces moderate rainfall but dissipates within 30 minutes. Maximum cloud mass remains limited because precipitation removes condensate before it can accumulate aloft.